Love, glass, and stones

Sculptor Alena Matějka travels from South Bohemia to the world and back again

Series: How UMPRUM graduates fare abroad

At the turning point around 1989, a strong generation of young artists began to study at UMPRUM. Thanks to their newfound freedom, students were able to make full use not only of their talent but also of the influence that the newly established heads of the studio from among the best and most independent-minded Czech artists had on them. Among the artists of the glass studio of Professor Vladimír Kopecký was Alena Matějka.

During her studies, Alena Matějka's unorthodox works combining glass and stone received international acclaim, which opened up previously unforeseen horizons for her.

What motivated you to study at UMPRUM?

I couldn't imagine a future other than being an artist. Everything was heading that way, although there were many obstacles standing in the way before the revolution. I was finally accepted to UMPRUM for the fifth time. As a freshman, I experienced many revolutionary days there. The wait was worth it. I then studied under Professor Kopecký, whom the students chose themselves. It was the best thing that could have happened to me in my professional career, especially since it was at the very beginning.

As a student, you created, among other things, trophies made of stone and glass, for which you received international prizes.

Yes, in Italy and Denmark. I bought my first kiln with the money I received. It gave me a push. We were all successful, and Kopecký's studio was very prominent. We had a lot of exhibitions that were written about and that made us known immediately. The fact that we were from Kopecký's studio helped us a lot.

Goblets

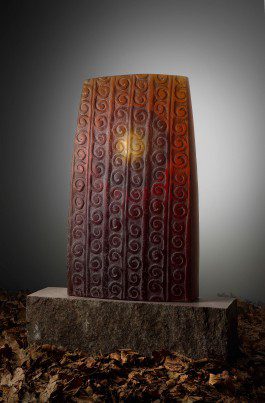

Stele

Path, installation in the Kamenice nad Lipou Chateau

Wasn't it harder after graduation?

No, because it seemed normal to me and many others to support themselves while studying. After UMPRUM I made a small series of different objects, glasses, and cups. There was always a project that provided financial support, I didn't feel a big burden.

I assume that you, like all of us young people in the 90s, travelled a lot.

After the revolution, we immediately ventured out into the world, because we had longed for it before and could not imagine such a possibility.

Alena Matějka with Prof. Vladimír Kopecký

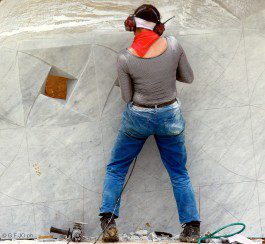

Glass casting

Why did you choose Glasgow for your UMPRUM internship?

Because it was the first exchange program in the study department that was offered at the time. I was supposed to study glass, but when I got to Glasgow I found there wasn't any. But I was always thinking about glass, travelling all over Scotland and taking impressions from medieval gravestones, which I converted into glass objects when I got back home.

You've always been attracted to working with stone.

Stone is everywhere in Kamenický Šenov, where I went to high school. I used to travel to the glass factories there when I was studying at UMPRUM. I was roaming around the basalt quarries and in one of them, suddenly in the fog and almost in the dark, I saw my finished thesis: columns with crystal.

Your diploma project made of several tons of stone and glass presented at Vyšehrad in the Gorlice Hall to this day remains a great success.

I worked exceedingly hard on that project, there were times when I thought I would not manage to complete it. A Czech lady living in Sweden came to the exhibition and invited me to a granite symposium based on the work. I wanted to work in stone, but I didn't know how to do it at all. I made my first-ever sculpture there, it ended up weighing about seven tons. I struggled a lot, I couldn't have done it at all without the help of a German sculptor. At the end of the symposium, I met the Swedish sculptor Lars Widenfalk, my future husband. I returned to Sweden and Lars started teaching me with stone. Love, life, stones. I started to enjoy stone tremendously because it is much more fun to work with than glass. I started to make stone sculptures and cast them in glass. Lars liked it and got into it too. I learned stone from him and he learned glass from me. It all came together nicely.

Most of the works you have made so far are impressive not only as art but also in how large, massive and heavy they are.

Small sculptures don't work for me, Lars once asked me why I didn't try doing smaller things. He gave me two beautiful little stones from Sweden, almost semi-precious stones. I worked on them for hours into the evening. It was stupid and small, and I threw them in the bushes.

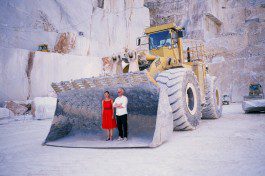

Alena Matějka in Italy

Was it your love of Michelangelo that brought you to the Italian marble quarries like so many other artists?

I travelled there because of my Michelangelo - Lars, who had worked there every year since he was a student at the academy. We went to Pietrasanta, a paradise for sculptors from all over the world, for twenty years. The most skilled Italian stone sculptors work there for famous artists or for those who can afford to pay them. Then there are those like us who make our own sculptures in rented workshops. A roof over head, a table, electricity, and air, that's enough. But in recent years, the town has started to flourish, turning stone studios into wine shops, boutiques, and galleries for tourists. Muddy sidewalks were replaced by white marble and everything went to hell. The stonemasons and sculptors were pushed out of the city into industrial zones with tin workshops, where they all had to be locked up so as not to disturb with dust and noise. We liked the former romance of having a studio only a hundred and fifty metres from the piazza, having a coffee or a glass of wine, and then going back to work.

Sadly, the various Montmartres of the world are coming to a similar end.

We have already found another one, in the south, where we can work again during the winter, because it is more pleasant than being cooped up somewhere at home with snow all around.

Alena Matějka with Lars Widenfalk in an Italian marble quarry

The Sea between Us

You have been living in Sweden and Jindřichův Hradec for two decades. Everything must be intertwined and influence each other.

It is a great gift for our art. Moving is just a bit of a challenge. We go from one forest to another forest, but since there is no plane from our forest to their Swedish forest, we have to drive. It's a long way, three days by car. On the first day, we drive to the sea and spend the night mostly in the car, on the second day we arrive at my brother's place in Upsalla, where we get a good meal and a warm bed. And then we arrive at Lars' cabin by a lake in the middle of Sweden. Lars used to have a house there, but he decided he didn't want to keep houses in two places.

You have participated in several ice symposia in Sweden.

Twice, but the conditions are brutal, each day around minus 20, you work like a lunatic. And it's dark, only the floodlights are on.

Are the ice symposiums just recreation for the participants or do the artists consider them artistic events? The ice object in which you froze roses can undoubtedly be considered art.

I consider everything I touch to be art. Even a cake I bake and decorate I consider art. I make it in a way that pleases me. It's my artistic expression. Everything you do, you have to do it to the best of your ability, even if it's just a cake.

A bed of roses in ice

In Bohemia, you live in Betlém near Mnich.

I am from there, I grew up in Kamenice nad Lipou. The house belonged to my grandmother and grandfather, my dad was born there and I inherited the house. We didn't look for the house, it found us on its own. My ancestors chose a beautiful place on the first hill in Vysočina, with a view of the Šumava Mountains, but they only looked at the ground and grew potatoes.

You and Lars have been trying to transform and cultivate the house and the surrounding landscape for years.

We're building our house ourselves, out of stone. One could say that it is a large joint sculpture. And there's a half-kilometre-long linden alley leading to the house, which we planted in 2006.

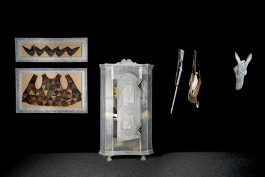

You were inspired by Sweden in your work My Dear, hunter from Lavondyss.

I made an elk head out of glass, an old wardrobe, a rifle, and a hunting vest out of feathers. My Lars is an elk hunter, but he doesn't want to hunt anymore, he started feeling sorry for the animals. Instead of elk meat, we have a pig slaughter every year in Bethlehem. Lars doesn't like that either, but I do because we trade a field we own with a neighbor for a pig. He has a field to use and we have a pig to slaughter every year.

My Dear, hunter from Lavondyss

This must have prompted you to create a large all-glass table with a pig slaughter feast, for which you received an award in the prestigious European competition Coburger Glaspreis in 2014.

I think they liked the feast because the Germans like pigs as much as we do.

Feast

You spent many months on a creative residency in Sunderland, UK.

The University of Sunderland under the auspices of the British Council was seeking by tender an artist to do some teaching there. I came to England in an old VW Golf with a holey fender. It was great, I often worked until midnight because I liked the quiet.

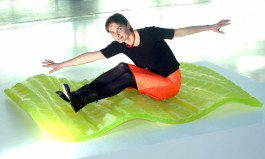

The result was huge glass flying carpets that were much talked and written about.

The University had a big furnace and it was a challenge for me to do something right in it. The flying carpets were then selected for an exhibition in Venice and one of them made it all the way to Barcelona, where it now looks across the boulevard at Antoni Gaudí's famous chimneys.

Magic carpet

How do you divide your year? Are you more in the Czech Republic or in the north?

More here. Especially now, after covid, we are looking forward to the south again. One leaves behind the practical everyday errands puts them behind and can fully concentrate on work in the new environment.

In our conversation, we travelled around a good chunk of Europe. But where is the place you mentioned that you want to go there to create?

Lars and I have our eye on an island in Greece, the marble there is like sugar, the whitest in the world!

Mgr.A. Alena Matějka, Ph.D. (*26.1.1966 Jindřichův Hradec) glass artist, a graduate of the Secondary School of Glassmaking in Kamenický Šenov (1981-1985, glass grinding department), VŠUP (1989–1997, Glass Studio, prof. Vladimír Kopecký) and doctoral studies at the same university (2000–2006). She drew attention to herself with her monumental diploma work The Path installed in the Gorlice Hall in Prague's Vyšehrad (now permanently exhibited in the cellars of the chateau in Kamenice nad Lipou, which belongs to the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague). She combined glass with pieces of basalt (e.g. Goblets, 1995-1999). She is devoted to cast glass sculpture and sculptural work with stone. She is often inspired by mysterious ancient cultures and their rituals, the environment of our ancestors, and nature. In cooperation with the Institute of Chemical Process Fundamentals, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, she experimented technologically with glass melting in a microwave oven. She has additionally taught intermittently in England, Japan, China, and the USA. Her works are exhibited in several public and private art collections in the Czech Republic and abroad. She has exhibited individually in the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Sweden, Great Britain, Austria, the USA, and Japan and in nearly one hundred and fifty collective exhibitions in various parts of the world.

Awards:

2014 Special Jury Award, Coburg Prize for Contemporary Glass, Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg, Germany

2005 Award for dignified representation of the Czech Republic at the World Exhibition EXPO 2005 in Aichi, Japan

2000 František Wolf Annual Award of the Czech Fund of Fine Arts, Czech Republic

1997 First Prize at the Young Glass (Michael Bang Award), Glasmuseet, Ebeltoft, Denmark

1996 First Prize at the exhibition of art colleges “Venezia Aperto Vetro ’96”, MuseoVetrario, Murano, Venice, Italy

Interview conducted by Milan Hlaveš

Interviews with successful graduates of UMPRUM within the framework of the Czech Presidency's of the The Council of the European Union were supported by the Centralized Development Projects of the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Czech Republic.