DOCTORATE IN THE MATTER OF DAGUERREOTYPE

Interview with Ondřej Přibyl by Lada Hubatová-Vacková

Signs of Causality (2009–2012) was part of Ondřej Přibyl's dissertation project at the Department of Graphic Arts and Visual Communication at UMPRUM in Prague. The doctoral research project focused on the investigation of the uniqueness and reproduction of the photographic image and the process of daguerreotype. It consisted of the mastery of the historical photographic process of the daguerreotype and the possibilities of transposing this technological method with a specific visuality into contemporary photographic work. The final outcome of the dissertation was an exhibition (UM Gallery, 2011) and a revised publication of the text part of the doctoral project (UMPRUM Publishing House, 2014).

What was the most important during your Ph.D. studies and practical outcomes? How does Ondřej Přibyl look back on his doctoral years at UMPRUM? On the occasion of the opening of the new Ph.D. programme at UMPRUM in English, we are publishing an interview with Ondřej Přibyl by art historian Lada Hubatová-Vacková.

Why did you decide to dedicate your doctoral project to the daguerreotype, an old photographic process from 1849?

I would say it was after some analysis. I struggled with photography for a long time during my studies because I didn't find it material enough, and I often wondered how to appropriately approach my photographs from the pure image to the subject. I realised that the daguerreotype accentuates what interests me about photography, i.e. above all the singularity, which is always somehow present in photography but is usually deeply hidden behind a layer of mechanical reproduction. What is very important for me in daguerreotype is the exacerbated material correlation of the photographic image with its referent. Each daguerreotype plate literally stood face to face with the one whose light trace is captured on it. The daguerreotype, on the other hand, does not contain, or very much resists, what has always rather discouraged or even annoyed me about photography, which again is mainly the possibility of infinite reproducibility at the cost of being detached from that necessary singular subject that disappears completely in digital photography. For me, the daguerreotype process represented an - almost elegant - solution to exploit the qualities of photography that interest me and avoid those that discourage me. At the same time, the daguerreotype, because of its properties, can be a very good reference point for thinking about the photographic medium as such. Daguerreotypes are a fascinating subject for me, we can see the image as a positive and as a negative, and at the same time see our own reflection in the mirrored surface.

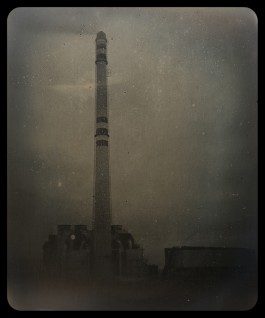

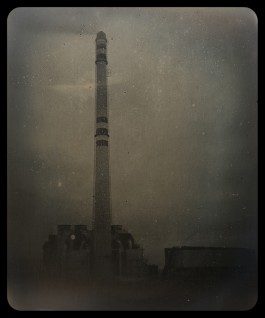

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 201111, daguerreotype, ,1 cm × 9 cm

In the selected daguerreotypes, the artist has deliberately chosen an industrial building in Prague-Malešice, which is used for the disposal and transformation of municipal waste. Through the daguerreotype image, the utilitarian building with an exceptionally long chimney is transformed into a memento of the impermanence of things. The sophisticated photographic technology on the unique daguerreotype plate that perpetuates this transience is a valid part of the overall work. The plates are finished with gilding.

Did you perceive the complicated technological process of the daguerreotype as an obstacle?

To avoid any misunderstanding, it should be noted that the technological process was really only one part of my doctoral project. The other part was to figure out how to deal with the daguerreotype as a medium that is distinctly different from the vast majority of other photographic techniques. Thus, an essential part of the practical outcome of my dissertation was to examine what can be photographed using daguerreotypes and how daguerreotypes behave differently from conventional techniques. The form is not irrelevant and if we encounter a certain motif, for example, on a large-format black-and-white photograph and the same motif on a colour Polaroid, it will be absolutely clear that even though the motif is the same, the statement will be completely different. However, the fact that it was a technological challenge was a rather strong motivation for me. Not many people master this process, and at that time I didn't know anyone in the Czech Republic who was doing it. I certainly suspected a community of daguerreotypists in America, where they pay more attention to historical techniques. There are also quite a lot of materials detailing the daguerreotype process, but there is always something missing and is very difficult to understand without experience. And it's not too surprising, the principle itself is simple, but the actual implementation hides a lot of intricacies and problems. So I really felt it was a technological challenge, and I soon realised that it would be, that I wouldn't simply read a manual. In the case of the daguerreotype, it was a fairly complex technical problem; I had to make a lot of gadgets, jigs, and processors and do a lot of testing. The very idea that it would be complicated and what I might have to do didn't put me off, on the other hand, I had no idea that it would be so horrible in places. I cursed myself a few times for creating such a challenging task.

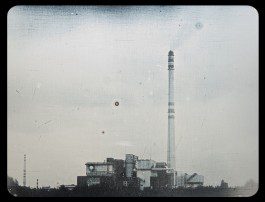

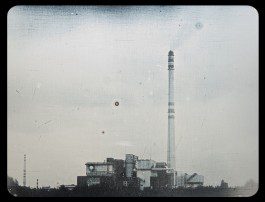

Ondřej Přibyl, Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 6,2 cm × 8,5 cm

Can you specify what was the most difficult part of the technological process?

For example, for a long time, I was addressing the problem of cleanliness on the surface of the board. It is necessary to achieve a mirror-like polish on the surface of the silver of the highest possible purity and at the same time maximum cleanliness. It's a question of how to remove all the polishing residue from the plate, it has to be clean on a molecular level. At the molecular level, we are creating a reaction and if there are any impurities present, they act as a barrier to the process and create unsightly relics, something that shouldn't be there in my view. We can certainly pretend that all the mistakes are intentional, but I like to control that if possible. Retouching daguerreotypes is not possible, and moreover, every sub-step is crucial and irreversible. It's quite easy to make a mistake in each step that will result in the final image either not being clear at all or so damaged that it's unusable.

How should one treat the medium? What is (or better: do you think is) specific to the daguerreotype?

I am convinced that it is a distinctly different language from the language of photography as we are used to it. The daguerreotype works in a strangely different way. I've noticed, for example, that motifs that would work well in a conventional black and white photograph, for example, look strangely banal or exaggerated or perhaps even kitschy in the small mirror of a daguerreotype plate, and conversely, things that I would have thought would look banal or too generic and contentless in a large colour photograph, the daguerreotype can impart a kind of almost magical rarity. It is not clear-cut, we are on rather thin ice in regard to feelings and tastes. After all, the fact that the daguerreotype is the oldest photographic method in use and therefore, for example, in portraits, there is a high probability that the subject is more than a hundred years dead.

Did you have the opportunity to consult your dissertation with experts from the photographic community, or even outside the artistic profession? Was the doctoral study supportive in terms of inter-institutional collaboration?

For the practical part, no one among photographers could give me much advice. But the fact that I was a Ph.D. student and that I had a specific institution behind me was clearly supportive, it was my ticket to consulting at various professional departments, for example at the VŠCHT in the Department of Inorganic Chemistry. Every time I said I was a Ph.D. student from UMPRUM, I was no longer just a person off the street with weird questions. And as much as they looked at me with slight astonishment when I told them that I was not a chemist and didn't know much about chemistry, but that I needed to figure this out, they were always extremely accommodating, although with a certain condescending smile, which certainly wouldn't have been so easy if I didn't have the institution of my school behind me. For example, I consulted metallographers about the cleanliness of the surface of a daguerreotype plate when I was trying to find out why a certain type of defect was forming on the plate and I needed to see how it looked under a microscope and to discover why the defects were there. I also discussed polishing with the metallographers, which is one of the cornerstones of the process.

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 6 cm × 8 cm

I assume you had to deal with the safety of the whole process from the beginning.

Absolutely. I consulted with chemists about the real dangers of the process and how to avoid them, how to avoid forgetting something - I wasn't planning on poisoning myself. From the beginning, I was working with the mercury process (with mercury vapor) and there you have to be extremely cautious, which I say as a warning to anyone interested in the process. Other consultations with chemists involved conservation, and I worked with restorers to preserve the daguerreotypes.

Were you in contact with foreign daguerreotypists?

I consulted with a lot of different experts, but I didn't consult any daguerreotypists directly. But I did do various research, gathering both historical records and various manuals, including those by contemporary American daguerreotypists, and some have procedures nicely documented, which was very helpful. But as I said, I always found that manuals are never complete, I never found any comprehensive instructions, even though it sometimes looked like that at first. I didn't learn from another daguerreotypist, which may have been a mistake and I should have done things differently. But on the other hand, I tell myself that because of this I can usually recognize how the various technological dead ends manifest themselves and diagnose what is, for example, degradation and what is a normal part of the process. It's quite a delicate process, precarious and unstable, especially if one doesn't engage in it on a daily routine basis, perhaps like in historical daguerreotype studios.

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 12,5 cm × 17 cm

So the historic, spectacular gift to the world that was Daguerre's manual did not represent a clear, easily replicable procedure?

It's hard to say. I suppose he gave the world a principle, but how exactly that principle is applied in practice may not have been part of the gift. I have set myself the practical task of wanting to put that principle into practice again, personally, here and at this time. In short, to learn it.

How was the doctoral programme at UMPRUM supportive? With whom did you consult your work on an ongoing basis?

For me, the doctoral studies were most supportive in the theoretical part. At that time I consulted with almost all the teachers of the Department of Theory and History of Art. From each of the teachers I was given topics that were somehow related to my project and that I had to think about, then discuss with them, it was wonderful. For example, Pavla Pečinková challenged me a bit on the writing, but it significantly helped me to clarify what I was doing, why I was doing it, how photography relates to other media, etc. I was forced to read crucial literature that I hadn't read before. If I hadn't been accepted to the Ph.D. program, I would certainly have explored daguerreotype as well, but I certainly wouldn't have written the x number of essays that became the basis for the theoretical part of my dissertation and then the book published by UMPRUM. I guess what I appreciate most about my whole doctoral studies is that I was forced to finish the whole thing and do it consistently.

I understand, when faced with opposition one is forced to refine unclear things, we all face natural laziness.

I think that even if I had been more consistent myself, I still wouldn't have gotten the kind of impulses that I got from the teachers at UMPRUM; those consultations were very important, they made me think things through much more deeply, much more broadly. Fundamentally, it shifted my thinking about the topics I was and still am engaged in. I'm afraid that even with my utmost will, I couldn't have achieved what I did through self-education; that contact is absolutely crucial.

Ondřej Přibyl, Signs of Causality. The Process of Daguerreotype, 2011, exhibition presentation of the dissertation project, Prague, UM Gallery, Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague.

Are you continuing to systematically explore these historical techniques?

I would say that I am ready to use any technique at any time, not only historical but any technique if I deem it appropriate and expedient. I'm going to continue to use historical photographic techniques as well, but I guess I wouldn't dare call it research. However, I daresay that given the daguerreotype training, I may be able to work with techniques I am not yet familiar with more confidence and without major floundering. But it's always a certain amount of discovery.

How have you used the skills acquired from your doctoral studies in practice?

It's impossible to generalize, but I'm sure that's why I got a great job working on several replicas of the rarest daguerreotypes found in Bohemia. These were the first Czech daguerreotypes such as the Old Post Office by Ignác Flora Stasek, for the Litomyšl museum where Stasek worked, his first Czech microdaguerreotype Cutting the Stem of a Plant, and the so-called Kynžvart daguerreotype, where I made a replica for the National Technical Museum. It's a plate that Daguerre himself made, Still Life from the Sculptor's Studio, and dedicated to Prince Metternich. The plaque was part of his large collection housed at Kynžvart Castle.

Ondřej Přibyl, Singularity and Reproduction of the Photographic Image, Praha: UMPRUM 2014, paperback edition, 139 pages, 8°, graphic design by Jan Čumlivski.

The publication presents a revised and supplemented theoretical part of the author's dissertation, in which he deals with the issue of what constitutes an original photographic image for the viewer and the creator, and how the perception of the status of the original and uniqueness has changed and is changing along with the development of photography and photographic technology. In this context, the author seeks to delineate the possibilities of defining the characteristics of the artistic medium and to raise the question of the extent to which the process of the creation of the artwork is included in the work itself. The old photographic technology of the daguerreotype, which is a kind of ultimate or reference point for the whole field of photography, serves as one of the pillars of this thinking. It can be regarded as such a point, especially given the resistance of the daguerreotype to mechanical reproducibility and the direct material correlation it maintains with the object whose light trace it captures. A look at such a point can serve to deepen our understanding of the whole field of photography as a technology and an image medium. The theoretical part is divided into eight units, in which the author mentions the historical context of the invention of photography and its establishment in the art world, demonstrates with the example of the technique of the photogram the complexity of the precise definition of the invention of photography, including its exact dating, etc. In the following chapters, the author deals with the question of whether or not photography is an image and whether it is treated as a sign, the concept of originality and reproduction concerning the autonomy of the photographic image, finding the boundary between copy and fake in the technological environment of the medium of photography, and finally the technology of daguerreotype.

Can you make a living from your work?

I am a photographer and I make a living from photography, which I studied at UMPRUM before my Ph.D. studies, and the daguerreotype technique is clearly part of that.

Was there anything missing in your doctoral studies where you felt you had some reserves?

I could probably stand more pressure and more consistency. Today I think to myself that if, for example, one of the teachers had said to me good attempt, but write the text again and better, I certainly wouldn't have wanted to, but in the end, I would undoubtedly have been happy and it would have been legitimate.

Ondřej Přibyl (1978, Prague) completed his MA studies at UMPRUM in Prague in the studio of Pavel Štecha and Ivan Pinkava, and his Ph.D. studies under the supervision of his supervisor Martina Pachmanová. He completed internships at the Studio of Typeface and Graphic Design under the supervision of Prof. Rostislav Vaněk and at the Studio of Visual Communication at UdK Berlin. He is a member of the art formation kunstWerk. He lives and works in Prague and its vicinity.

Lada Hubatová-Vacková (1969, Opava) is an art historian, curator of exhibitions, works at the Department of Theory and History of Art, and is the head of the Centre for Doctoral Studies at UMPRUM in Prague.

DOCTORATE IN THE MATTER OF DAGUERREOTYPE

Interview with Ondřej Přibyl by Lada Hubatová-Vacková

Signs of Causality (2009–2012) was part of Ondřej Přibyl's dissertation project at the Department of Graphic Arts and Visual Communication at UMPRUM in Prague. The doctoral research project focused on the investigation of the uniqueness and reproduction of the photographic image and the process of daguerreotype. It consisted of the mastery of the historical photographic process of the daguerreotype and the possibilities of transposing this technological method with a specific visuality into contemporary photographic work. The final outcome of the dissertation was an exhibition (UM Gallery, 2011) and a revised publication of the text part of the doctoral project (UMPRUM Publishing House, 2014).

What was the most important during your Ph.D. studies and practical outcomes? How does Ondřej Přibyl look back on his doctoral years at UMPRUM? On the occasion of the opening of the new Ph.D. programme at UMPRUM in English, we are publishing an interview with Ondřej Přibyl by art historian Lada Hubatová-Vacková.

Why did you decide to dedicate your doctoral project to the daguerreotype, an old photographic process from 1849?

I would say it was after some analysis. I struggled with photography for a long time during my studies because I didn't find it material enough, and I often wondered how to appropriately approach my photographs from the pure image to the subject. I realised that the daguerreotype accentuates what interests me about photography, i.e. above all the singularity, which is always somehow present in photography but is usually deeply hidden behind a layer of mechanical reproduction. What is very important for me in daguerreotype is the exacerbated material correlation of the photographic image with its referent. Each daguerreotype plate literally stood face to face with the one whose light trace is captured on it. The daguerreotype, on the other hand, does not contain, or very much resists, what has always rather discouraged or even annoyed me about photography, which again is mainly the possibility of infinite reproducibility at the cost of being detached from that necessary singular subject that disappears completely in digital photography. For me, the daguerreotype process represented an - almost elegant - solution to exploit the qualities of photography that interest me and avoid those that discourage me. At the same time, the daguerreotype, because of its properties, can be a very good reference point for thinking about the photographic medium as such. Daguerreotypes are a fascinating subject for me, we can see the image as a positive and as a negative, and at the same time see our own reflection in the mirrored surface.

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 201111, daguerreotype, ,1 cm × 9 cm

In the selected daguerreotypes, the artist has deliberately chosen an industrial building in Prague-Malešice, which is used for the disposal and transformation of municipal waste. Through the daguerreotype image, the utilitarian building with an exceptionally long chimney is transformed into a memento of the impermanence of things. The sophisticated photographic technology on the unique daguerreotype plate that perpetuates this transience is a valid part of the overall work. The plates are finished with gilding.

Did you perceive the complicated technological process of the daguerreotype as an obstacle?

To avoid any misunderstanding, it should be noted that the technological process was really only one part of my doctoral project. The other part was to figure out how to deal with the daguerreotype as a medium that is distinctly different from the vast majority of other photographic techniques. Thus, an essential part of the practical outcome of my dissertation was to examine what can be photographed using daguerreotypes and how daguerreotypes behave differently from conventional techniques. The form is not irrelevant and if we encounter a certain motif, for example, on a large-format black-and-white photograph and the same motif on a colour Polaroid, it will be absolutely clear that even though the motif is the same, the statement will be completely different. However, the fact that it was a technological challenge was a rather strong motivation for me. Not many people master this process, and at that time I didn't know anyone in the Czech Republic who was doing it. I certainly suspected a community of daguerreotypists in America, where they pay more attention to historical techniques. There are also quite a lot of materials detailing the daguerreotype process, but there is always something missing and is very difficult to understand without experience. And it's not too surprising, the principle itself is simple, but the actual implementation hides a lot of intricacies and problems. So I really felt it was a technological challenge, and I soon realised that it would be, that I wouldn't simply read a manual. In the case of the daguerreotype, it was a fairly complex technical problem; I had to make a lot of gadgets, jigs, and processors and do a lot of testing. The very idea that it would be complicated and what I might have to do didn't put me off, on the other hand, I had no idea that it would be so horrible in places. I cursed myself a few times for creating such a challenging task.

Ondřej Přibyl, Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 6,2 cm × 8,5 cm

Can you specify what was the most difficult part of the technological process?

For example, for a long time, I was addressing the problem of cleanliness on the surface of the board. It is necessary to achieve a mirror-like polish on the surface of the silver of the highest possible purity and at the same time maximum cleanliness. It's a question of how to remove all the polishing residue from the plate, it has to be clean on a molecular level. At the molecular level, we are creating a reaction and if there are any impurities present, they act as a barrier to the process and create unsightly relics, something that shouldn't be there in my view. We can certainly pretend that all the mistakes are intentional, but I like to control that if possible. Retouching daguerreotypes is not possible, and moreover, every sub-step is crucial and irreversible. It's quite easy to make a mistake in each step that will result in the final image either not being clear at all or so damaged that it's unusable.

How should one treat the medium? What is (or better: do you think is) specific to the daguerreotype?

I am convinced that it is a distinctly different language from the language of photography as we are used to it. The daguerreotype works in a strangely different way. I've noticed, for example, that motifs that would work well in a conventional black and white photograph, for example, look strangely banal or exaggerated or perhaps even kitschy in the small mirror of a daguerreotype plate, and conversely, things that I would have thought would look banal or too generic and contentless in a large colour photograph, the daguerreotype can impart a kind of almost magical rarity. It is not clear-cut, we are on rather thin ice in regard to feelings and tastes. After all, the fact that the daguerreotype is the oldest photographic method in use and therefore, for example, in portraits, there is a high probability that the subject is more than a hundred years dead.

Did you have the opportunity to consult your dissertation with experts from the photographic community, or even outside the artistic profession? Was the doctoral study supportive in terms of inter-institutional collaboration?

For the practical part, no one among photographers could give me much advice. But the fact that I was a Ph.D. student and that I had a specific institution behind me was clearly supportive, it was my ticket to consulting at various professional departments, for example at the VŠCHT in the Department of Inorganic Chemistry. Every time I said I was a Ph.D. student from UMPRUM, I was no longer just a person off the street with weird questions. And as much as they looked at me with slight astonishment when I told them that I was not a chemist and didn't know much about chemistry, but that I needed to figure this out, they were always extremely accommodating, although with a certain condescending smile, which certainly wouldn't have been so easy if I didn't have the institution of my school behind me. For example, I consulted metallographers about the cleanliness of the surface of a daguerreotype plate when I was trying to find out why a certain type of defect was forming on the plate and I needed to see how it looked under a microscope and to discover why the defects were there. I also discussed polishing with the metallographers, which is one of the cornerstones of the process.

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 6 cm × 8 cm

I assume you had to deal with the safety of the whole process from the beginning.

Absolutely. I consulted with chemists about the real dangers of the process and how to avoid them, how to avoid forgetting something - I wasn't planning on poisoning myself. From the beginning, I was working with the mercury process (with mercury vapor) and there you have to be extremely cautious, which I say as a warning to anyone interested in the process. Other consultations with chemists involved conservation, and I worked with restorers to preserve the daguerreotypes.

Were you in contact with foreign daguerreotypists?

I consulted with a lot of different experts, but I didn't consult any daguerreotypists directly. But I did do various research, gathering both historical records and various manuals, including those by contemporary American daguerreotypists, and some have procedures nicely documented, which was very helpful. But as I said, I always found that manuals are never complete, I never found any comprehensive instructions, even though it sometimes looked like that at first. I didn't learn from another daguerreotypist, which may have been a mistake and I should have done things differently. But on the other hand, I tell myself that because of this I can usually recognize how the various technological dead ends manifest themselves and diagnose what is, for example, degradation and what is a normal part of the process. It's quite a delicate process, precarious and unstable, especially if one doesn't engage in it on a daily routine basis, perhaps like in historical daguerreotype studios.

Signs of Causality (Waste incinerator, Malešice), 2011, daguerreotype, 12,5 cm × 17 cm

So the historic, spectacular gift to the world that was Daguerre's manual did not represent a clear, easily replicable procedure?

It's hard to say. I suppose he gave the world a principle, but how exactly that principle is applied in practice may not have been part of the gift. I have set myself the practical task of wanting to put that principle into practice again, personally, here and at this time. In short, to learn it.

How was the doctoral programme at UMPRUM supportive? With whom did you consult your work on an ongoing basis?

For me, the doctoral studies were most supportive in the theoretical part. At that time I consulted with almost all the teachers of the Department of Theory and History of Art. From each of the teachers I was given topics that were somehow related to my project and that I had to think about, then discuss with them, it was wonderful. For example, Pavla Pečinková challenged me a bit on the writing, but it significantly helped me to clarify what I was doing, why I was doing it, how photography relates to other media, etc. I was forced to read crucial literature that I hadn't read before. If I hadn't been accepted to the Ph.D. program, I would certainly have explored daguerreotype as well, but I certainly wouldn't have written the x number of essays that became the basis for the theoretical part of my dissertation and then the book published by UMPRUM. I guess what I appreciate most about my whole doctoral studies is that I was forced to finish the whole thing and do it consistently.

I understand, when faced with opposition one is forced to refine unclear things, we all face natural laziness.

I think that even if I had been more consistent myself, I still wouldn't have gotten the kind of impulses that I got from the teachers at UMPRUM; those consultations were very important, they made me think things through much more deeply, much more broadly. Fundamentally, it shifted my thinking about the topics I was and still am engaged in. I'm afraid that even with my utmost will, I couldn't have achieved what I did through self-education; that contact is absolutely crucial.

Ondřej Přibyl, Signs of Causality. The Process of Daguerreotype, 2011, exhibition presentation of the dissertation project, Prague, UM Gallery, Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague.

Are you continuing to systematically explore these historical techniques?

I would say that I am ready to use any technique at any time, not only historical but any technique if I deem it appropriate and expedient. I'm going to continue to use historical photographic techniques as well, but I guess I wouldn't dare call it research. However, I daresay that given the daguerreotype training, I may be able to work with techniques I am not yet familiar with more confidence and without major floundering. But it's always a certain amount of discovery.

How have you used the skills acquired from your doctoral studies in practice?

It's impossible to generalize, but I'm sure that's why I got a great job working on several replicas of the rarest daguerreotypes found in Bohemia. These were the first Czech daguerreotypes such as the Old Post Office by Ignác Flora Stasek, for the Litomyšl museum where Stasek worked, his first Czech microdaguerreotype Cutting the Stem of a Plant, and the so-called Kynžvart daguerreotype, where I made a replica for the National Technical Museum. It's a plate that Daguerre himself made, Still Life from the Sculptor's Studio, and dedicated to Prince Metternich. The plaque was part of his large collection housed at Kynžvart Castle.

Ondřej Přibyl, Singularity and Reproduction of the Photographic Image, Praha: UMPRUM 2014, paperback edition, 139 pages, 8°, graphic design by Jan Čumlivski.

The publication presents a revised and supplemented theoretical part of the author's dissertation, in which he deals with the issue of what constitutes an original photographic image for the viewer and the creator, and how the perception of the status of the original and uniqueness has changed and is changing along with the development of photography and photographic technology. In this context, the author seeks to delineate the possibilities of defining the characteristics of the artistic medium and to raise the question of the extent to which the process of the creation of the artwork is included in the work itself. The old photographic technology of the daguerreotype, which is a kind of ultimate or reference point for the whole field of photography, serves as one of the pillars of this thinking. It can be regarded as such a point, especially given the resistance of the daguerreotype to mechanical reproducibility and the direct material correlation it maintains with the object whose light trace it captures. A look at such a point can serve to deepen our understanding of the whole field of photography as a technology and an image medium. The theoretical part is divided into eight units, in which the author mentions the historical context of the invention of photography and its establishment in the art world, demonstrates with the example of the technique of the photogram the complexity of the precise definition of the invention of photography, including its exact dating, etc. In the following chapters, the author deals with the question of whether or not photography is an image and whether it is treated as a sign, the concept of originality and reproduction concerning the autonomy of the photographic image, finding the boundary between copy and fake in the technological environment of the medium of photography, and finally the technology of daguerreotype.

Can you make a living from your work?

I am a photographer and I make a living from photography, which I studied at UMPRUM before my Ph.D. studies, and the daguerreotype technique is clearly part of that.

Was there anything missing in your doctoral studies where you felt you had some reserves?

I could probably stand more pressure and more consistency. Today I think to myself that if, for example, one of the teachers had said to me good attempt, but write the text again and better, I certainly wouldn't have wanted to, but in the end, I would undoubtedly have been happy and it would have been legitimate.

Ondřej Přibyl (1978, Prague) completed his MA studies at UMPRUM in Prague in the studio of Pavel Štecha and Ivan Pinkava, and his Ph.D. studies under the supervision of his supervisor Martina Pachmanová. He completed internships at the Studio of Typeface and Graphic Design under the supervision of Prof. Rostislav Vaněk and at the Studio of Visual Communication at UdK Berlin. He is a member of the art formation kunstWerk. He lives and works in Prague and its vicinity.

Lada Hubatová-Vacková (1969, Opava) is an art historian, curator of exhibitions, works at the Department of Theory and History of Art, and is the head of the Centre for Doctoral Studies at UMPRUM in Prague.