I'd like to work on something that I haven't encountered before

Jan Čtvrtník is a product designer who, in the past two decades since graduating from university, has successfully worked for several world-famous brands of industrial products. He says that what he enjoys about design is getting information and finding open spaces that no one has tried before.

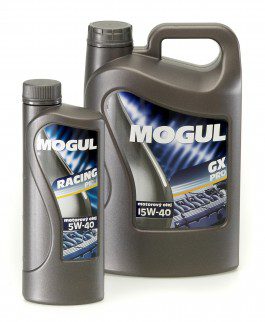

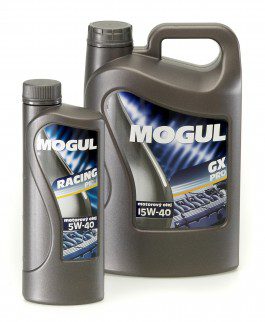

Packaging for engine oil, Paramo Pardubice, 2004, photo from the designer's archive

Why did you decide to study at UMPRUM?

I went to college after military service. It was there, in between the tires in 1994, that I found out I had to go back to school. UMPRUM was my dream institution, but I missed the deadline for the entrance exams because of the military, so I started at the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice Faculty of Education. In my third year, I won the Model Young Package Competition and that directed me to UMPRUM again.

I spent the first two semesters in Zlin, where I caught up with the departing professors, and then moved on to product design at Olgoi Chorchoj. They represented the young blood no longer affected by communism and running off to Europe. Everything was possible, everything was open, or so we thought. I enjoyed it a lot, we had a great group in the studio, and we still see each other to this day. My classmates are doing a lot of good stuff and that makes them great competition.

But graduation from UMPRUM was not the end of your education.

I decided to go abroad and by chance, I got a scholarship from the founder of IKEA for students from Eastern Europe to study in Sweden. They sent me and a colleague to work at the IKEA development centre. We quickly found out that it was an exclusive opportunity where even Swedes don't get to go. We were very lucky. This was followed by a project with NASA Space Center. Something I'd wanted to do for a long time. The theme was the 2020 moon landing. If math matters a lot in conventional product design, it matters a thousand times more in space exploration. Space is about lives, and lives are the most important thing. Only then does the science and all the other stuff come in. We learned a ton of information there.

After Sweden, I decided to go to London with my girlfriend. It's a design mecca, but it's also an insanely competitive environment. I had a good portfolio, but no relevant references in England, so it didn't really work out. I eventually found an advert that Electrolux was looking for designers, I applied, went through the interview process and instead of returning to Sweden to their design centre, I was surprised and delighted to find myself in Italy. It was 2007, so only three years out of school, but as you can see, it wasn't a straight path for me. After seven years of working there, the company was closing its Italian design studio and moving everything to Stockholm.

I didn't really want to go back to Sweden, it would have been a very harsh climate adjustment after Italy. I had three different offers at the time, but I wanted to go back to the Czech Republic because we already had children and I missed our humour and I was socially isolated from my friends. It turned out differently. Now I'm in Liebherr, Germany, where I joined as the first in-house designer. There was never any designer here, it was handled through freelancers. We've been living in Germany for years, in Swabia, which is renowned for being insular, even more so than Sweden. With my wife and three children, we have "our Czech cluster", we work together for each other.

Tivoli, IKEA, 2007, photo from the designer's archive

Which geographical area would you recommend to other designers?

Professionally, the environment in Scandinavian countries and Finland is great for a designer, despite the darkness and cold. I would probably recommend Finland the most, where design is an integral part of life, society, and national identity. In the North, they lay down and engage in creative thinking everywhere. Design is everything and for everyone. In Sweden, when we lived there, there were 15 times as many design graduates coming out of design schools every year compared to the Czech Republic with the same population. Of course, they don't all find jobs as designers, but they become product developers, for example, who shape design not in terms of aesthetics but in terms of function. This then helps designers to create in the best possible way, while at the same time design thinking appears in unexpected places.

Rings, Tactoo, 2003, photo Petr Holub

The prevailing range of conventional appliance stores, regardless of brand, tends to be visually boring and lacking in design innovation. Why is that?

Conservative customers are comfortable with so-called major appliances. White is the main colour, in recent years quite a lot of stainless steel, and carbon steel is starting to break through, but other colours rarely do. Many people would like them, but there are so many colours and shades that it would mean a huge number of variations. Production and logistics costs would rise enormously and so would the consumer price. Few units would be sold and overall such production would not be worthwhile.

It is strategically advantageous for large corporations in the electrical appliance sector to make their products look like they come from one brand. This is different from, say, seating furniture, where each designer is often required to give the furniture a distinctive character.

Design is very much linked to product management, which calculates and analyses customer behaviour, what they will buy and what they won't. According to projections, parts of society in cities may not even have a fridge or dishwasher in the future; they will not cook but eat out or have food delivered, which can be cheaper than renting an apartment with a kitchen.

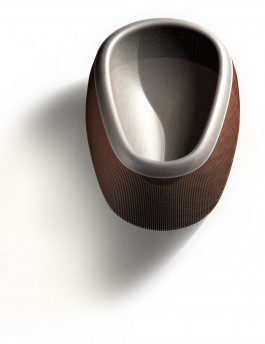

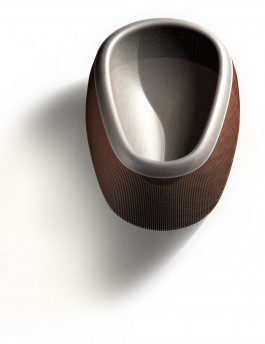

Koxy armchair, MM Interiéry, 2004, photo from the designer's archive

Sofa Jota-jota, Polstrin, 2011, photo from the designer's archive

But that doesn't give the designer many opportunities to exercise creativity?

Unlimited creativity is more of a fine art matter. An industrial designer cannot let his imagination run wild; he must be creative and imaginative within the narrow confines of strict parameters. At the end of the day, all that is left is to try to emotionally highlight the connection to the brand. Apart from the details inside, what can be discussed more fundamentally are the doors, and even then only for freestanding devices, not at all for built-in ones. Despite this enormous complexity, many designers can't get past it.

For example, a round fridge may be impressive and admired, but it is highly impractical in terms of space and capacity. It would sell poorly and end up stuck with low production run numbers. Something similar happened with Zanussi's Oz fridges. They were publicised everywhere, but sales were a flop. I experienced this in furniture with my chair Koxy. I did myself a favor recently and bought one chair second-hand. It got a lot of press back in the day, I got an award for it, but very few sold. Now I own one!

Droog Aalto Vase, 2007, photo from the designer's archive

Twist Vase, Moser, 2008, photo from the designer's archive

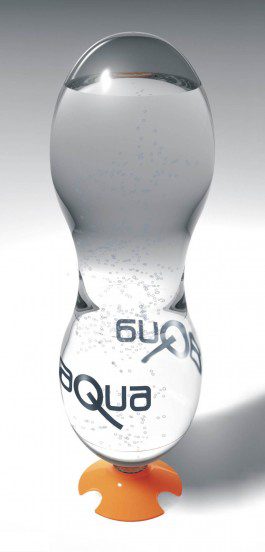

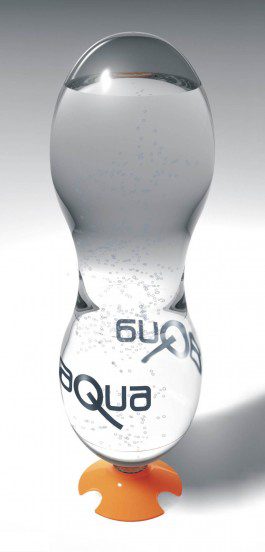

Pet bottle Aqua, co-author

Filip Streit, 2002, designer's rendering

People think that consumer electronic companies use "built-in obsolescence". Is it true that they exist?

I haven't noticed anything like that in Electrolux or Liebherr, on the contrary, everything is tested in hundreds of thousands of load cycles in laboratories and professionally evaluated. If something breaks quickly, it tends to be the lower price level of the products at different companies, where they save on material.

My grandmother had the same refrigerator for almost forty years. Why don't you see much of that anymore?

This is the next level of our consumer life. We're planning for the fridge to last at least fifteen years. But what will last that long in the kitchen? If you don't have a solid wood countertop, you want a new one eventually. You're gonna keep the old fridge? You'll probably replace it, too. A fridge is a dumb slave that, when it's working, you're happy with, once it stops, it's usually thrown away. It gets old visually, it goes out of style. Like movies or clothes. You can see right away that it's the 70s, 80s, or 90s. There's also a massive shift in electricity requirements today. People routinely buy a new fridge after five to seven years because it's just expensive to run. They calculate what appliance is worth owning in terms of consumption.

Monolith refrigerator, Liebherr, 2018, photo from the designer's archive

What do you think is good design and how do you get there?

Good design has to be economically well thought out, it has to function well, look good, be easy to produce and of course be sellable. When designing a glass vase or seat, a few parameters are enough, above all, to make the thing likable. With industrial design, it's more complicated. There's a lot of balancing to be done, as soon as one parameter changes, other parameters are affected. I would compare it to trying to balance a thousand pans on a set of scales, you change one of them and it in turn reduces, for example, consumption, but somewhere because of five other pans that correspond to other parameters another pan pops up and upsets the balance. It is necessary to balance all of the parameters to match one another.

Will you reveal your future plans?

Starting next year, I'll be working part-time and looking at what's next. I'm thinking about a Ph.D. I'm tempted to try my hand at user-centered design, designing by observing user habits. And teach a bit while doing my Ph.D. We'll see. I want to force myself to think a little differently, to go a little deeper into something. I'm scared of my work becoming a routine that I don't even enjoy anymore. I wish to grow naturally and at the same time to pass on my experience to others, to shorten the path, to make them understand more quickly where the path can lead and where it doesn't.

Flowerpot Calimera, Plastia, 2010, photo Kristina Hrabětová

Rattan tub, 2000, designer's rendering

Radiator Hoop, 2007, designer's rendering

I'm gonna ask you one last, kind of tabloid question. Do you have a dream project you'd like to propose?

I was asked the same question when I was interviewed around the time of my thesis twenty years ago. At the time, I wanted to work for NASA. That came true. Currently, I don't have anything, in particular, to fire off without thinking. I would like to do something I haven't encountered before, studying a lot of things to understand complete relationships, how it's going to be produced, at what price level, imagining where it's going to be sold, who's going to buy the product and how it's going to work, and so on, there's an awful lot that goes into industrial design, and you have to get it into your head all at once. What I enjoy about the process is getting information and finding open spaces where no one has tried something before.

MgA. et Mgr. Jan Čtvrtník (1975 in Českých Budějovicích) Lives and works in Tannheim and Ochsenhausen (GER).

Studies: 2004-2006 Ingvar Kamprad Design Center (IKDC), Faculty of Engineering, Lund University, Sweden; 2002-2003 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Peru; 2001 Häme Polytechnic, Häme University of Applied Sciences (HAMK), Hämenlinna, Finland; 1998-2004 Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague (VŠUP/UMPRUM), in Zlín, Industrial Design Studio, prof. Pavel Škarka, and since 1999 in Prague the Product Design Studio of Michal Froňek and Jan Němeček - Olgoj Chorchoj; 1995-2000 Faculty of Education, University of South Bohemia (PF JU), České Budějovice; 1989-1993 Secondary School of Applied Arts, Prague, studio of Promotional Graphics.

Career: 2014-present, Senior designer, Liebherr, Home Appliances Division (GER); 2012-2014 Lead designer, AEG (ITA); 2012-2019 Design director, Zoxcall/Simphonie (CZE); 2011-2014 Lead exhaust hood designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2010-2014 Senior designer, AEG, Electrolux (ITA); 2009-2014 Senior designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2007-2009 Designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2007 cooperation with Lunar Design Studio, All-in-one PC for HP (USA); 2005 intern - designer, IKEA design centre (SWE); 2005 member of the Star Design project, JSC NASA, Houston (USA); 2003-present, founding member of the Tactoo project (CZE); 2002-2007 founding member of File design studio (CZE).

Awards (selection): 2021 Red Dot Design Award Best of the Best, with team Liebherr (GER); 2009 Grand Designer of the Year and Czech Designer of the Year 2008, Czech Grand Design (CZE); 2008 First place in the Droog Design Climate Competition, Droog Design (NED); 2006 Outstanding design, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2005 Design of the Year (student category), Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2004 Ingvar Kamprad Scholarship, Lund University (SWE); 2003 first prize in the Czech Chair design competition, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2003 Good Design (with Filip Streit), Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2002 Outstanding design, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2001 first place in the Eta-Vize, competition, Eta (CZE); 2001 Good Design Award, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 1996 Winning the 1st year of the Model Young Package competition (CZE).

Interview conducted by Milan Hlaveš

The article was created as part of the project Priorities of the Czech Presidency, supported by the Centralized Development Projects of the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Czech Republic.

I'd like to work on something that I haven't encountered before

Jan Čtvrtník is a product designer who, in the past two decades since graduating from university, has successfully worked for several world-famous brands of industrial products. He says that what he enjoys about design is getting information and finding open spaces that no one has tried before.

Packaging for engine oil, Paramo Pardubice, 2004, photo from the designer's archive

Why did you decide to study at UMPRUM?

I went to college after military service. It was there, in between the tires in 1994, that I found out I had to go back to school. UMPRUM was my dream institution, but I missed the deadline for the entrance exams because of the military, so I started at the University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice Faculty of Education. In my third year, I won the Model Young Package Competition and that directed me to UMPRUM again.

I spent the first two semesters in Zlin, where I caught up with the departing professors, and then moved on to product design at Olgoi Chorchoj. They represented the young blood no longer affected by communism and running off to Europe. Everything was possible, everything was open, or so we thought. I enjoyed it a lot, we had a great group in the studio, and we still see each other to this day. My classmates are doing a lot of good stuff and that makes them great competition.

But graduation from UMPRUM was not the end of your education.

I decided to go abroad and by chance, I got a scholarship from the founder of IKEA for students from Eastern Europe to study in Sweden. They sent me and a colleague to work at the IKEA development centre. We quickly found out that it was an exclusive opportunity where even Swedes don't get to go. We were very lucky. This was followed by a project with NASA Space Center. Something I'd wanted to do for a long time. The theme was the 2020 moon landing. If math matters a lot in conventional product design, it matters a thousand times more in space exploration. Space is about lives, and lives are the most important thing. Only then does the science and all the other stuff come in. We learned a ton of information there.

After Sweden, I decided to go to London with my girlfriend. It's a design mecca, but it's also an insanely competitive environment. I had a good portfolio, but no relevant references in England, so it didn't really work out. I eventually found an advert that Electrolux was looking for designers, I applied, went through the interview process and instead of returning to Sweden to their design centre, I was surprised and delighted to find myself in Italy. It was 2007, so only three years out of school, but as you can see, it wasn't a straight path for me. After seven years of working there, the company was closing its Italian design studio and moving everything to Stockholm.

I didn't really want to go back to Sweden, it would have been a very harsh climate adjustment after Italy. I had three different offers at the time, but I wanted to go back to the Czech Republic because we already had children and I missed our humour and I was socially isolated from my friends. It turned out differently. Now I'm in Liebherr, Germany, where I joined as the first in-house designer. There was never any designer here, it was handled through freelancers. We've been living in Germany for years, in Swabia, which is renowned for being insular, even more so than Sweden. With my wife and three children, we have "our Czech cluster", we work together for each other.

Tivoli, IKEA, 2007, photo from the designer's archive

Which geographical area would you recommend to other designers?

Professionally, the environment in Scandinavian countries and Finland is great for a designer, despite the darkness and cold. I would probably recommend Finland the most, where design is an integral part of life, society, and national identity. In the North, they lay down and engage in creative thinking everywhere. Design is everything and for everyone. In Sweden, when we lived there, there were 15 times as many design graduates coming out of design schools every year compared to the Czech Republic with the same population. Of course, they don't all find jobs as designers, but they become product developers, for example, who shape design not in terms of aesthetics but in terms of function. This then helps designers to create in the best possible way, while at the same time design thinking appears in unexpected places.

Rings, Tactoo, 2003, photo Petr Holub

The prevailing range of conventional appliance stores, regardless of brand, tends to be visually boring and lacking in design innovation. Why is that?

Conservative customers are comfortable with so-called major appliances. White is the main colour, in recent years quite a lot of stainless steel, and carbon steel is starting to break through, but other colours rarely do. Many people would like them, but there are so many colours and shades that it would mean a huge number of variations. Production and logistics costs would rise enormously and so would the consumer price. Few units would be sold and overall such production would not be worthwhile.

It is strategically advantageous for large corporations in the electrical appliance sector to make their products look like they come from one brand. This is different from, say, seating furniture, where each designer is often required to give the furniture a distinctive character.

Design is very much linked to product management, which calculates and analyses customer behaviour, what they will buy and what they won't. According to projections, parts of society in cities may not even have a fridge or dishwasher in the future; they will not cook but eat out or have food delivered, which can be cheaper than renting an apartment with a kitchen.

Koxy armchair, MM Interiéry, 2004, photo from the designer's archive

Sofa Jota-jota, Polstrin, 2011, photo from the designer's archive

But that doesn't give the designer many opportunities to exercise creativity?

Unlimited creativity is more of a fine art matter. An industrial designer cannot let his imagination run wild; he must be creative and imaginative within the narrow confines of strict parameters. At the end of the day, all that is left is to try to emotionally highlight the connection to the brand. Apart from the details inside, what can be discussed more fundamentally are the doors, and even then only for freestanding devices, not at all for built-in ones. Despite this enormous complexity, many designers can't get past it.

For example, a round fridge may be impressive and admired, but it is highly impractical in terms of space and capacity. It would sell poorly and end up stuck with low production run numbers. Something similar happened with Zanussi's Oz fridges. They were publicised everywhere, but sales were a flop. I experienced this in furniture with my chair Koxy. I did myself a favor recently and bought one chair second-hand. It got a lot of press back in the day, I got an award for it, but very few sold. Now I own one!

Droog Aalto Vase, 2007, photo from the designer's archive

Twist Vase, Moser, 2008, photo from the designer's archive

Pet bottle Aqua, co-author

Filip Streit, 2002, designer's rendering

People think that consumer electronic companies use "built-in obsolescence". Is it true that they exist?

I haven't noticed anything like that in Electrolux or Liebherr, on the contrary, everything is tested in hundreds of thousands of load cycles in laboratories and professionally evaluated. If something breaks quickly, it tends to be the lower price level of the products at different companies, where they save on material.

My grandmother had the same refrigerator for almost forty years. Why don't you see much of that anymore?

This is the next level of our consumer life. We're planning for the fridge to last at least fifteen years. But what will last that long in the kitchen? If you don't have a solid wood countertop, you want a new one eventually. You're gonna keep the old fridge? You'll probably replace it, too. A fridge is a dumb slave that, when it's working, you're happy with, once it stops, it's usually thrown away. It gets old visually, it goes out of style. Like movies or clothes. You can see right away that it's the 70s, 80s, or 90s. There's also a massive shift in electricity requirements today. People routinely buy a new fridge after five to seven years because it's just expensive to run. They calculate what appliance is worth owning in terms of consumption.

Monolith refrigerator, Liebherr, 2018, photo from the designer's archive

What do you think is good design and how do you get there?

Good design has to be economically well thought out, it has to function well, look good, be easy to produce and of course be sellable. When designing a glass vase or seat, a few parameters are enough, above all, to make the thing likable. With industrial design, it's more complicated. There's a lot of balancing to be done, as soon as one parameter changes, other parameters are affected. I would compare it to trying to balance a thousand pans on a set of scales, you change one of them and it in turn reduces, for example, consumption, but somewhere because of five other pans that correspond to other parameters another pan pops up and upsets the balance. It is necessary to balance all of the parameters to match one another.

Will you reveal your future plans?

Starting next year, I'll be working part-time and looking at what's next. I'm thinking about a Ph.D. I'm tempted to try my hand at user-centered design, designing by observing user habits. And teach a bit while doing my Ph.D. We'll see. I want to force myself to think a little differently, to go a little deeper into something. I'm scared of my work becoming a routine that I don't even enjoy anymore. I wish to grow naturally and at the same time to pass on my experience to others, to shorten the path, to make them understand more quickly where the path can lead and where it doesn't.

Flowerpot Calimera, Plastia, 2010, photo Kristina Hrabětová

Rattan tub, 2000, designer's rendering

Radiator Hoop, 2007, designer's rendering

I'm gonna ask you one last, kind of tabloid question. Do you have a dream project you'd like to propose?

I was asked the same question when I was interviewed around the time of my thesis twenty years ago. At the time, I wanted to work for NASA. That came true. Currently, I don't have anything, in particular, to fire off without thinking. I would like to do something I haven't encountered before, studying a lot of things to understand complete relationships, how it's going to be produced, at what price level, imagining where it's going to be sold, who's going to buy the product and how it's going to work, and so on, there's an awful lot that goes into industrial design, and you have to get it into your head all at once. What I enjoy about the process is getting information and finding open spaces where no one has tried something before.

MgA. et Mgr. Jan Čtvrtník (1975 in Českých Budějovicích) Lives and works in Tannheim and Ochsenhausen (GER).

Studies: 2004-2006 Ingvar Kamprad Design Center (IKDC), Faculty of Engineering, Lund University, Sweden; 2002-2003 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Peru; 2001 Häme Polytechnic, Häme University of Applied Sciences (HAMK), Hämenlinna, Finland; 1998-2004 Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague (VŠUP/UMPRUM), in Zlín, Industrial Design Studio, prof. Pavel Škarka, and since 1999 in Prague the Product Design Studio of Michal Froňek and Jan Němeček - Olgoj Chorchoj; 1995-2000 Faculty of Education, University of South Bohemia (PF JU), České Budějovice; 1989-1993 Secondary School of Applied Arts, Prague, studio of Promotional Graphics.

Career: 2014-present, Senior designer, Liebherr, Home Appliances Division (GER); 2012-2014 Lead designer, AEG (ITA); 2012-2019 Design director, Zoxcall/Simphonie (CZE); 2011-2014 Lead exhaust hood designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2010-2014 Senior designer, AEG, Electrolux (ITA); 2009-2014 Senior designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2007-2009 Designer, Electrolux (ITA); 2007 cooperation with Lunar Design Studio, All-in-one PC for HP (USA); 2005 intern - designer, IKEA design centre (SWE); 2005 member of the Star Design project, JSC NASA, Houston (USA); 2003-present, founding member of the Tactoo project (CZE); 2002-2007 founding member of File design studio (CZE).

Awards (selection): 2021 Red Dot Design Award Best of the Best, with team Liebherr (GER); 2009 Grand Designer of the Year and Czech Designer of the Year 2008, Czech Grand Design (CZE); 2008 First place in the Droog Design Climate Competition, Droog Design (NED); 2006 Outstanding design, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2005 Design of the Year (student category), Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2004 Ingvar Kamprad Scholarship, Lund University (SWE); 2003 first prize in the Czech Chair design competition, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2003 Good Design (with Filip Streit), Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2002 Outstanding design, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 2001 first place in the Eta-Vize, competition, Eta (CZE); 2001 Good Design Award, Design Centre of the Czech Republic (CZE); 1996 Winning the 1st year of the Model Young Package competition (CZE).

Interview conducted by Milan Hlaveš

The article was created as part of the project Priorities of the Czech Presidency, supported by the Centralized Development Projects of the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Czech Republic.